The tree whisperer is back.

You may remember Kathy Wolf from earlier in the season. She’s a research social scientist at the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences and UW’s Nature and Health Initiative. Nature-based human health, environmental psychology, and urban ecosystems are her jam.

We loved our conversation with her so much, we decided to release it in full. She shares how trees affect our physical and mental health, how just a few minutes in nature can positively impact us, and what she would do with a magic wand that could change our world.

Rooted‘s host and executive producer is Kyle Norris. Our editor is Mary Heisey. You can find out more at forterra.org/rooted. And you can contact us at marketing@forterra.org

Find additional episodes here.

More on Kathy Wolf

https://www.washington.edu/news/people/kathleen-wolf/

Music in this episode

Sam Barsh: No Link

Episode Transcript

Kyle Norris: It turns out spending 15 minutes in a park, around trees & greenery makes us healthier. And can really help improve our mental health. In this episode we hear from someone who has dedicated her life to studying the science behind this connection.

This is “Rooted, where we stand.” A podcast from Forterra. I’m your host Kyle Norris.

I spoke with social scientist Kathy Wolf From the University of Washington. She was in another episode we did for a story about tree canopies.

And this is our entire conversation you’re about to hear.

I wanted to know what Kathy has learned about the connection between humans and nature. And ultimately, why that matters. And what’s at stake with all this.

We met at Volunteer Park in Seattle. Kathy rolled up on her bicycle. Which she showed me, is the kind you can fold down and collapse and then carry it around.

We sat on a park bench surrounded by cool trees.

Our interview was fun and informative and I thought other people would enjoy the whole conversation.

Oh and I did not originally record my questions, I only recorded Kathy’s answers. So I later recorded my questions and inserted them into this interview. So you may hear a little sound difference between Kathy and myself.

I started by asking Kathy to set the stage, and explain the difference between trees and tree canopies.

Kathy Wolf: Well of course, trees–I mean around us now–look at what we’ve got these beautiful beech trees, lum the lily, poplar, hollies and all sorts of things. So there are individual trees that have individual character, age, shape, form. But then, “canopy” is sort of this consolidate, it’s the bird eye view of the trees as you imagine going over them.

And why do we talk about canopy? Because it’s a measure many cities use now, it’s kind of a benchmark of the extent & the health of the urban forest.

KN: Ok to back up, can you explain where we are sitting? Because people can’t see where we are & we’re in a pretty cool place.

KW: We really are, we’re in a park in Seattle, Washington. Volunteer Park for people who might know it. And it’s an arboretum, it’s not only a park. But it has been over the years a very deliberate collection of different trees. Some of them native to PNW, some of them come from places all over the world.

KN: Let’s talk about our tree canopy. How’s our canopy in Seattle?

KW: I would say Seattle is very actively pursuing canopy increase. And if I recall the last assessment done was 5 years ago, I think it was at 26%. Let me just say that. Mid to low 20s. Um, in residential areas a little higher is better. Um, a prominent urban forester and international scholar has just released a recommendation for urban planning, for urban forestry and it’s the 3/30/300 rule: that every person is able to see 3 trees from their home

That there’s 30% canopy over residential areas. And that every person is within 300 yards of a park or open space.

So if we look at 30% as kind of an international standard, it’s ambitious. Um, Seattle is doing fairly well.

KN: Can you clarify what that 30% part means?

KW: Yeah again, if you think of a bird’s eye view. This is often done with remote sensing, maybe satellite data. There’s a technology called lidar people fly over in airplanes and send a signal that bounces back & you estimate canopy. But it’s basically just think of the cut out of the edges of all the trees & vegetation as you’re looking at it in 2 dimension. That’s a rather simplistic way to describe, but that’s pretty much what it becomes as a metric.

And within that, arborists look closely at the age structure of the canopy–that is are the trees mostly old or young? Are they mixed aged, which is optimal. They look at the species distribution. Because you don’t want a monoculture, if a disease comes through and wipes out your entire canopy in a short amount of time that’s not great either.

So there’s that first cut of that aerial view but within there’s additional detail arborists pay attention to.

KN: So to recap, the percentage is what you see from a bird’s eye view of the trees?

KW: Yeah, yeah & larger vegetation, shrubs, anyway, yeah that’s it.

KN: This story I’m doing is in South Seattle, for students who live next to the airport. Any sense of how their tree canopy is doing?

KW: Ya know I haven’t looked at that. I know the city of Seattle within its boundaries has done a canopy assessment–that would be SeaTac, Burien area–I don’t know if they’ve done a tree canopy assessment.

But I will say, what many cities have found, Settle included, is that there are disparities in the distribution of this canopy. That is there are socioeconomic or cultural centers or neighborhoods in communities that may not have an equal amount of canopy. This was kind of intuitively recognized for a long time. But in the past, the thought was, well, trees are pretty, if some people don’t have them it’s not a big deal.

Well now we know there are many services & functions provided by trees. Including human health. Including community benefit & welfare & so there’s much more attention to equity in tree canopy distribution. Which means, now more tree planting, more community engagement, more effort to reach out to communities and include them in planting & park planning.

KN: So how important is all of this?

KW: Oh, you’re asking someone who’s been studying this for decades! This is incredibly important. And it’s not just the canopies–canopy is the most coarse grain sort of baseline of how one assesses or measures the presence of trees.

But in my work I have been exploring how people respond at eye-level. On the ground, sitting on a bench as we are, looking out of their home, walking to school or work. And how they respond to trees and green & landscape in their everyday environment.

And this is profoundly important. That, again, we used to think this was about aesthetics, about beauty. Now we realize: mental health, physical health, social cohesion. All sorts of things are associated with these daily important encounters with trees & nature.

KN: Can you even go into that even more? Like how are trees affecting our health?

KW: Yeah, yeah, ok let’s start with mental health. During covid, we have seen in the news now for a variety of reasons associated with Covid , and there were mental health issues in various populations prior to covid…but we’re in a mental health crisis. People are hurting. Depression, tension, stress, all sorts of things.

And what we see is that even brief encounters, some of the earliest research about trees & health done in the 1980s, um, it’s really interesting to look at the articles cause there’s these little scientific charts. And within a matter of minutes, if people are stressed and see trees, not even walking through it, just simply looking at images, within minutes there’s stress reduction. And this is measured physiologically. Through heart rate, through what is called galvanic skin response. Uh, the moisture in your hands and other skin surfaces, whatever.

Other mental health–depression. People with clinical depression, there have been studies showing that time in nature, say 60 minutes or so roughly, there’s a reduction in the symptoms of depression.

ADHD. Children with ADHD who spend routine amounts of time outdoors, and this is brief, 30, 20 minutes, um show reduced ADHD symptoms. And this isn’t about moving around or physical activity. There appears to be some sort of response in the brain that helps kids to focus more, to pay closer attention to things, associated with time in nature.

KN: What do you think of trees?

KW: What do I think of trees?? (Laughs). I’ve been accused of being a tree hugger for a long time and I own it! I own it totally. And with all the research I’ve done, not only that but I continue to monitor the research being done all around the world, and it’s thousands of articles about nature and health response. And I’ve developed a different appreciation for trees. And particularly in cities–I love old gnarly trees! Because the standards now of our arbor culture are trees with a nice clean form, they’re well pruned, they grow, they don’t cause problems, right. I like old gnarly trees that remind us of time & age & culture & the change that takes place around us.

So, I get a lot of invitations to travel and do talk with professional groups and science groups and I like walking around cities I’ve never been to. And once in awhile I’ll encounter an old tree I’ve never encountered before. I’m kinda like a tree whisperer and I’ll think, what have you seen, what’s happened around you in the many decades you’ve been alive? So, ya know, it’s kind of a fantasy thing but not too far out there.

KN: You touched on this, but how do trees affect our brains?

KW: Well, um. There’s a little bit of neuroscience where people are literally in a lab or in some sort of monitoring or scanning device & they’re wired up. I don’t remember the details, but what we do see when people look at highly built images vs images having nature in them, different parts of the brain respond. And so there’s something that goes on, we’re not sure how it relates to these health outcomes. This would be known in science as a pathway. So we see these responses of nature & health, we don’t quite know all the mechanisms, the neuroscience mechanisms.

But what, one theory that is prominent in all of this is attention restoration theory. And this is the idea that our brains & bodies did not evolve to where we are now, where we focus so long on tasks. Focus on a monitor, focus on a budget, focus on a report. Our minds have been doing that in relatively recent times. So we become fatigued, and maybe you’ve had this experience? I certainly do and I watch myself for it. You experience this cognitive fatigue and it starts to be expressed as a body fatigue.

And you may feel frustrated or you may feel like you’re not thinking straight. And there’s even studies recognizing impulse control is reduced and aggression may actually be increased. So these studies show that time in nature, brief amounts of time and you don’t have to go far away to the mountains or ocean, just your backyard or neighborhood park, helps to restore that attention, that cognitive attention. And facilitate, then, return to the work you need to do. Be it a school kid or someone in the office, whatever.

And this plays out in a number of ways in our lives. Sometimes we just overextend ourselves cognitively. There’s so many demands on our attention. Our phones, texts, notifications, the kids! Ya know, things at work & home & school. So nature is potentially an anecdote for all of that.

KN: You mentioned young people. How do trees & nature affect the health of young people?

KW: Well there’s been, a lot of studies about nature & health have focused on adults but there’s a good bit on young people. If we start with very young children, there’s some interesting work being done on the health of our microbiome–our gut health. And one ecologist calls these elements in our environment– “old friends.” And so children need exposure to soil, plants, tree bark, because they take in parts, microorganisms from these materials and it helps develop that healthy microbiome. And with that comes better immune systems, perhaps resistance to asthma, all sorts of ongoing consequences as a child ages.

Then I mentioned ADHD. Kids are a little older. Ya know, cognitive performance, there appears to be some value of routine nature experiences for that.

There have been studies about school performance. Children, and some of the studies are about the landscape of the school–views from the classroom window. Or the landscape or forest canopy around the school. And each of these, it’s not entirely consistent, but many of these studies are showing better school performance in terms of standardized testing, graduation rates & things like that.

One really interesting study done at University of Illinois in Chicago. They did a series of studies a little over a decade ago in Chicago public housing. And one study they found was those public housing apartment buildings where teenagers were living that had green, compared to teenagers who were living in buildings totally surrounded by paved surfaces, there was more impulse control in girls who had this green in their environment. Why is this important? Because if we can control our impulse, think through our actions & make good choices–that can possibly lead to a series of better choices in our lives and our development.

KN: So this program I’m doing a story about is a program for teenagers in the Highline public schools. They planted trees in a cool little area & cleaned up a forest behind their school. And now the kids ask their math teacher if they can go outside into the forest to reset before taking a test. They students say being in this forest helps them transition from hallways to school. Sometimes their teachers lead them on meditations or forest baths–where they practice being in the present moment. Then they hug and thank a tree. So I’m just curious if you did anything like that in school?

KW: (Laughs) No, at least not within school. I grew up in the Tacoma area, a large family. Roman Catholic. I have 8 siblings. My father is a hunter, fisher, and hiker. We had those interludes on weekends, sometimes in evenings. I did not have that in school at all. But this is really encouraging to hear you describe this because it ties right back to attention restoration theory.

And you mentioned forest bathing, forest therapy. Some of the most robust research about trees & nature & health response has come from Japan & South Korea about forest bathing responses.

And what’s so important in that, not in like attention restoration theory, is mindfulness. Is the intentional screening of all these things that can distract one or take one away from thinking about what’s really important.

So test preparation–that is so cool. And I’d guess the students, once they discover this in school, may take it home, may take it back to their households, their siblings and help other people to discover this power of nature, this potential power of nature in their lives.

And the brief interlude–part of it is the mindfulness. I’m coming to explore, even though I’m semi-retired–ya know there’s so many questions in my mind about nature & health. And since we’re on this vein of mental health & function…I find that when I’m in nature, and I enjoy kayaking, I enjoy hiking & I find “mind wandering” is equally valuable to me.

And this is not–oh my phone I gotta pay attention to it or I’m thinking about my schedule. Mind wandering is simply letting my mind flow and letting it go where it wants to go. And of course there are seeds implanted based on projects I’m working on or problems I’m thinking about or a data analysis or something. But it’s not unlike the thoughts that come just before you go to sleep or in the shower. This mind wandering in nature I find very valuable and there’s very little in the science literature about that so I’m starting to explore a little bit.

KN: Remember when I asked how important this is and you said I’ve dedicated my life to it? Can you use a metaphor to convey how important trees & nature are to our health?

KW: Oh yea. This is something I’ve been talking about and thinking about in recent years. And a metaphor I’ve landed on is nutrition. So in our lives, think about food & meals. We sometimes have the occasional great feast–it might be Thanksgiving, it might be an anniversary event, a celebration. A bunch of people get together, friends & loved ones. We share great food, sometimes we all cook together, sometimes someone just lays out a beautiful spread that they so enjoyed doing. Alright, that’s one type of meal. And for me that’s equivalent to going to the coast for a backpacking trip. Or an overnight kayak paddle, right.

Then there’s some restaurant meals. Once in a while we go out, we have a nice meal with a friend or two or a loved one, and they’re nice too. And that might be a longer hike for me or a bike ride. I rode my bike here, might be a longer bike ride out in a nature area and enjoying that.

But what I see in this research literature is everyday nature is like everyday nutrition. We need vitamins, we need minerals, we need fiber. We need quality food to sustain us and help us perform at our best. And I’m coming to the conclusion that nature experiences are very similar. We might have the big feast, if you will, we might have the occasional special event, but we need everyday encounters with quality nature.

KN Who does not have access to trees? And who does this impact?

KW: Oh, that’s a complicated question. There’s in part…ok let me frame this in two ways. One is: there are people who simply don’t have access because of the absence of trees & parks. Ya know, I spoke a little earlier about the disparities in the distribution of tree canopy and parks. And the discoveries possible because of big data. We now have incredible computing power on our laptops. In my bike bag there I have a laptop that has computing power that excels computers that filled entire rooms decades agoright.

So people can do this big analysis of census data, socioeconomic data & compare to distribution of trees & parks & other vegetation & they see the disparities.

So the first is access: to assure or to work toward equitable access for everyone.

The second part is awareness of this. I don’t know how many times I’ve done a public presentation and there are some people like, “Oh yeah, it’s Dr Wolf again, she’s talking about nature and health.” But for other people it’s like an epiphany. And I can tell, when I’ve done a public talk and people line up and they chat and they have questions or comments. And sometimes people will approach me and they’re tearing up, and telling me about an experience they’ve had or an experience with a loved one or something in their work…and I’ve given them the evidence grounding, the numbers to go back and convince decision makers and convince people to invest in nature for health.

So one one hand it’s access and on the other hand it’s awareness in what one chooses to either introduce in one’s life or embrace in one’s life.

KN: With everything we’re talking about, what is at stake?

KW: Oh my gosh. Human health! Wellness. It’s not just nature in the city, it’s not just nice to have, it’s profoundly, profoundly, important. And we’re just now coming to realize this.

One of the projects I’m working on is with the American Planning Association. The national office of the APA in Chicago. And we’re attempting to do is lift this evidence of nature and health to an expression or guidelines for nature systems in cities. Of course that’s been going on for a while. But it’s pretty much a mayor’s office, or city managers–like, “Oh yeah go talk to parks & rec people. Oh yeah, go talk to the urban forester.”

What we’re talking about is elevating a nature system outlook that’s on par with utilities. It’s on par with transportation systems, it’s on par with discussions of housing. So the importance of this, we hope the evidence will elevate it to something, when major decisions and policies are made in cities it’s comparable. And we think about how we allocate space in the city for different needs and purposes.

KN: If I gave you a magic wand what would you do? I mean, go big.

KW: (Laughs) Ok first of all this APA project, we are wrestling with this. First I’d take the magic wand and create the report we can take into the world, not just the United States. But into the world. And within that then, what might we see in that project or in those guidelines?

Biodiversity. We need biodiversity in our cities, for a variety of reasons. For pollinators. For urban agriculture. For the health and well being of our urban forest. The canopy, the ongoing sustainability of it.

But, in addition to that, we need that variety in our lives. We need…What research shows–the integrity of this nature system. We don’t want monocultures. We don’t want boredom!

I have just returned from a trip in Peru. It was a combination of research and vacation trip. And we did, my husband and another friend did a trek through the Andes, back door into Machu Picchu. It was astounding.

But then returning to cities. What I recognized, a lot of Americans will tolerate incredibly boring spaces, incredibly uninteresting places and communities. So that’s part of the magic wand also, is introducing nature in a way, not only just to say ok now it’s there, it’s accessible. But in ways that are culturally interesting, in ways that are ecologically interesting.

In ways that reflect our bioregionalism. I mean why is the pacific northwest different from northern California? Different from the upper midwest? Different from NE Seaboard? How to encourage and promote the understanding and appreciation of the differences–the biological & ecological differences–in addition to these beneficial nature experiences.

KN: Can you paint me a visual of what you would want to see? Make it come to life.

KW: I’m a person who doesn’t do well imposing what I like on others. Let me frame it in a different way. Is, I would impose systems whereby we could explore localized expression of green. And what do I mean by that?

In this recognition of cultural and social economic disparities in tree distribution and park distribution–some of the initial responses of cities was: “Let’s go in there & just plant trees!” And that has not worked very well. We need engagement,we need relationship building. We don’t just treat trees as a technology but there as something that connects people. Where that has happened successfully I see remarkably interesting landscapes:

landscapes where people hang out, landscapes where people have cafes & meals, where kids have play structures not out of a catalog. So this local character and imprint is what I’m really interested and encouraged by.

KN: Do you have an example of that?

Let me see…ok there’s a place in eastern Washington. A colleague of mine with Trust for Public Land has done a project there. It’s a Mexican American community–1st, 2nd, 3rd multiple generation immigrants. They had this little pocket park basically neglected by the city. So the Trust for Public Land came in, built up some relationships with local partners & the city. In a highly engaged way with the community now, it’s a restored park or transformed park but it has elements of that culture.

What was one part of it?…I think a kioska, I think it’s called, which is a small meeting space which is typical in small Mexican communities. They have a performance space for young people, there’s a mariachi group and a young women’s dance group and now have outdoor space to perform. And this is in addition to some picnic spaces, tree spaces, play structure, etc.

So in this one instance it was not only the park itself and its physical expression, but it was this process of integration, communication, meetings, meals. I was once invited as this was all unfolding I was invited to be a part of a technical response group, and the night before the meeting we got together and all made tamales. Then had tamales the next day during lunch at the meeting. It’s this relationship building as a process of collaboration, in addition to what the park becomes.

KN: To recap, you’re saying ideas like this are where we should be headed?

KW: Those are places we should be headed. Absolutely. And I get the sense Forterra and other non-profits are on board with this. They’re realizing this. Where they used to be conservation groups largely ecological goals. “Well we’ll conserve that place. And do we want people there or not?” It’s really flipped to: how do acknowledge, conserve and engage, all at once. In ways that benefit the landscape but also benefit the human community.

KN: Why is it important that we engage?

Well first of all, there is health benefit in people being involved in these nature based collaborations. So other research that I’m aware of, has found that people who are lonely and socially isolated are more inclined to illness and disease. And if they are treated with a surgery or procedure, they don’t recover as quickly if they’re socially isolated. So there are physiological reasons. There are also reasons–you can’t call someone to assist you if you need help and so on.

So this process of place-creation based on nature or surrounding nature, aids people in greater social cohesion, reducing loneliness. And it builds power. This particular example in east Wenatchee what they found there was the voice of people was elevated in terms of communications with local government. To make their case about why they needed funding for this park. Why they needed the parks department to pay more attention to this place. So there’s a variety of community health benefits as well as individual health benefits associated with creating, collaborating and improving or building a brand new park.

KN: I’m going to look at my questions, have some water.

KW: Good idea, good idea.

KN: Can you make the connection between tree canopies and climate change?

KW: Oh, uh, How much time have we got? (laughs) Ok trees & climate change. I’ll focus on one consequence and that is–there are some people, scientists talk about urban trees and carbon sequestration, and frankly compared to largest forest reserves, the sequestration, the mitigation potential of urban trees is probably modest. I think the value of trees in cities, with regard to climate, is the adaptation, the response to climate change. And one of those is thermal comfort.

So there’s a lab at Portland State University. They have done heat mapping during peak heat events in Portland, they did it in Tacoma, I’m not sure if they’ve done it in Seattle yet.

But it’s a citizen science, they mobilize a group of people, they train them. Then when there’s a high heat event people are out doing measurements on a randomized location plot approach. What I’m seeing in the literature is the value of thermal refuge.

So here we are, we’re in a tree canopy. Look at the size of the beech tree right–how old is that baby?! That is providing and can provide thermal refuge. And so if we think about planting trees not in linear form or scattered, but thinking about planting them in ways that provide pockets of thermal regue. Because in high heat events not everyone has AC. Not everyone can stay in their apartment for days on end. So we need places of respite outdoors and trees play a role in that.

And what’s really interesting in this thermal refuge research is the effect of the trees–because of evapotranspiration and the effect on air quality and air temperature, there can be a plume of positive effect that extends beyond a forest grove or beyond a park.

So there are some cities–China is really on this. Technologically they’re on a lot of urban forestry for dense city solutions. And one of those is thinking of planting trees in a way that generates this thermal refuge that sort of carries over from tree pocket to tree pocket to tree pocket. Creating a larger area then of heat relief for people.

KN: Thermal relief, that means a cool place for humans?

That means a cool place for humans. It means a place where paved materials are shaded so they don’t heat up as much. What happens in these high heat events, is the paving materials collect heat and then they readmit it in the night so the night temperature doesn’t drop. So if you can prevent those paving materials from heating up, that’s another advantage of tree shade.

But basically yeah, hermal refuge is cooler places during hot times where people can be more comfortable.

KN: What compels you to study all this?

KW: Again, how much time do we have (laughs)

I’m asked that more & more often, because of increasing interest on the part of people and nature and health, and my age, as long as I’ve been doing this. Um, I’d say when I was young there was no clear sort of track. My professional career training has been a meander. I started out with a degree in biology, and that was here in Washington state. Then married soon after graduation.

Moved to Key West, Florida. I was the first urban forester for the city of Key West. I was working with landscape architects, that needed by law, by regulation, to use a certain amount of native plant material. And they had no clue because they were coming from offices in other parts of the country.

So I started working with them and thought, I kind of like this nexus of nature and culture. Nature and human society.

Went back to grad school, thought I’d become a landscape architect. But then took courses in environmental psychology from some pioneers in the field–Rachel and Steven Capland. And that was it! So I had a science overlay on the nature and culture blend.

So that. And some forest service funding early on in my career, a couple of grants started the momentum. Just like any other science, once you start doing research, you might answer one or two questions and you discover about twenty more and so on and on it goes.

KN: Do you dream of trees?

KW: I do. I do. On occasion I will have a remarkable tree experience. During Covid–my husband and a friend and I, we had been kayaking every weekend from the start of Covid. We knew this was not going to end quickly. In July we hit 1,000 miles–just day trips. Little paddles on Saturdays and Sundays. I have seen some incredible trees on the shorelines of the Salish Sea and I sometimes dream of them.

I have also been invited to be a vertical tree guide on a couple of occasions. Where arborists set up the rigging into a very tall tree and I accompany people as we move up into the tree and we talk about their emotions, their reactions, and I dream about that.

Because one time I climbed, well I didn’t climb, I was basically elevatored up by way of this climbing rig. To the top of 180 foot Douglas fir in Portland. And at the base, this tree is like a solid column, big diameter right. And you get up in the middle it’s a tangle of branches.

At the top it’s like a sapling, it moves in the wind. It switches back & forth which is at first kinda scary but is a remarkable experience and I occassionally have dreams about that.

KN: What have trees taught you?

KW: Patience. Things happen slowly. Work toward a general goal. Even if you don’t necessarily see progress. Stop and appreciate beauty. Just stop and put everything aside once in a while and just revel at what’s around you.

KN: Anything else I forgot to ask about or something you want to mention?

KW: Not really. I’ll just close by saying, where early on in my career my interest was more in the specific studies of nature and health response. Now, because of what I’ve learned doing that myself as well as the many other publications and studies that have been done…I’m far more interested in translating this research to policy and programs. To make it real, to make it practical, to make it have an influence on people’s lives. And I’m encouraged to see ever greater interest in that. Not only on the part of tree huggers or greenies, but people who are making key decisions in policy, budgets and how our communities are formed.

So I’m seeing a really encouraging transition in this realm at this time.

[Theme music]

KN: That was a conversation with social scientist Kathy Wolf. From the University of Washington’s school of environmental & forest sciences.

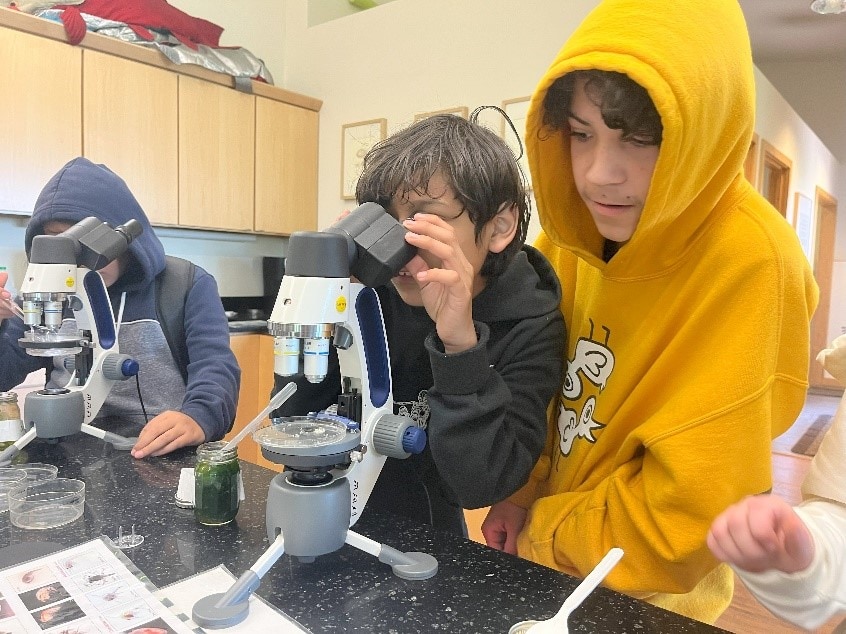

You can hear more of Kathy in our episode about tree canopies. Where we learn about a pilot program where teenagers planted more trees around their school. To enhance the tree canopy. And they also cleaned up a small madrone forest behind their school where they now go to meditate and recharge in the middle of their school day. We talk with one teenager who says the program has even helped her feel..less lonely.

“Rooted, where we stand” is a podcast from Forterra.

Rooted’s Host and Executive Producer is me, Kyle Norris. Our editor is Mary Heisey.

“Rooted” was created by Forterra. An unconventional land trust. Forterra envisions people and nature thriving together in a place where everyone belongs.

You can find out more at forterra dot org.