This is the fifth of a blog series highlighting Forterra’s history in anticipation of the organization’s rapidly approaching 35th anniversary. This is the start of a year of looking back to look forward, a concept honoring the Sankofa symbol of Ghana’s Akan Tribe which means we should not be afraid to look to our past to help plan our future. This Forterra history project delves into the people, cultures and changes and that shaped the region and the organization and includes historical anecdotes, interviews with visionaries, perspective pieces from a diverse range of experts and celebrates the learning-est moments in Forterra’s history from 1989 through yesterday evening.

Written by Topher Donahue

As the opportunities for preserving vast, pristine landscapes have dwindled, an unexpected metamorphosis is underway to transform some of our region’s timberland toward a future of innovative conservation practices and restoration. The 3,422-acre Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park is one of those places; a forest that has become an inspiring, if somewhat heartbreaking, story of conservation and restoration. The property’s evolution, from an industrial tree farm and mill site toward a resilient and diverse ecosystem, is just beginning, thanks to a surprising collaboration between Coast Salish Tribes, Kitsap County, recreationalists, local residents and conservation organizations.

The credit for the transformation is largely due to the land’s original stewards, the Port Gamble S’Klallam and Suquamish Tribes. The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe lived on the point of Port Gamble until 150 years ago, when a timber company decided to build a sawmill there and kicked the Tribe across the bay to live on a tidal flat where high tides flooded their homes. The sad moving day is recorded for perpetuity on the Tribe’s cultural history website: “The (Tribe) did not want to leave their homeland, their fishing sites and hunting territory; unfortunately, they were forcibly moved to the reservation anyway. With their canoes in tow, rounding ’Marrowstone Point, the canoes’ occupants, looking back at their ancestral homes, could see their village in flames, burning rapidly to the ground – by order of the Great White Father in Washington, D.C.’”

The sawmill operated until 1995. Due to the increasing pressures of suburban growth among lowland forests in the Northwest, the timber company decided it was time to let the area’s fourth crop of Douglas fir monoculture grow in order to build real estate value and rally community support behind a residential development. They platted the land into 20-acre residential lots – including areas used by the Tribes. When the residential development was announced, the Tribes saw a threat to the lands that gave them life – as well as an infringement on their treaty rights. The Treaty of Point Elliott enshrined Tribal access to their traditional fishing areas forever, and a residential development would essentially shut down their access to the area. They sounded the alarm with the weight of hundreds of generations of precedent and federal law behind them.

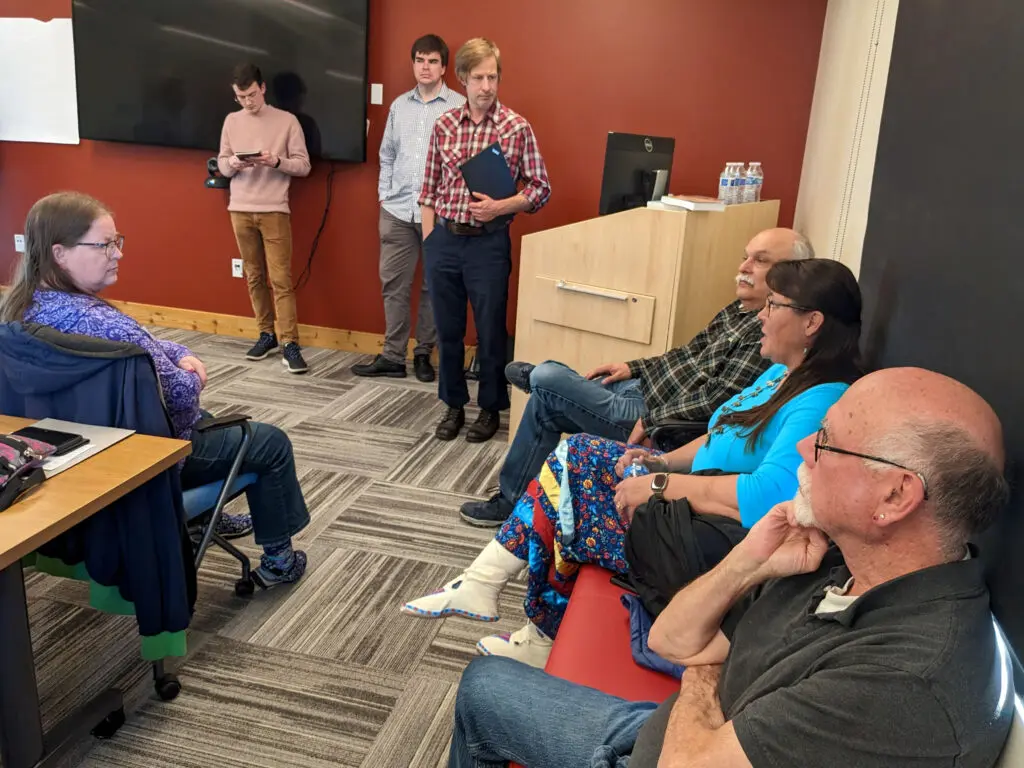

Refreshingly, unlike so many land conflicts, the Port Gamble story hasn’t been a fight so much as a quest to find solutions that are tenable to everyone involved. Port Gamble resident Judy Willott explained, “The (Kitsap Forest and Bay Coalition) grew from the Tribe and environmental groups to include, I’d have to say, even the timber company. It included mountain bike people, horseback people, people who just like to drive by and see trees, commercial groups – it’s a gigantic group.” From their very first meeting, Judy recalls that the coalition took a collaborative approach. A county planner organized the event and, as he had done for other events, spread out maps on tables for the different groups to mark up and capture their vision. “We all said, ‘No! No! No! Let’s all work on one map, right now, together!’ So, all of these groups gathered around one map. The key thing was that we said we’re going to do this together instead of everyone doing their separate thing.”

While some members of the coalition wanted to restore the forest to a healthy habitat within 100 years, others wanted trails, and some just wanted a park. The Tribes wanted what they’d always had – a place to practice their age-old lifestyle of gathering, hunting and fishing. And the company still wanted a development, but agreed to a more compact version that wouldn’t sprawl across thousands of acres and into crucial native food sources. Judy said, “So, everyone had a different vision, but they all coalesced into one point where we came to an agreement that we needed to buy the land and let the company harvest one more time.”

The reason for allowing the harvest was entirely economic; buying the timber and the land was prohibitively expensive (believe it or not, the timber was worth more than the land), so acquiring the underlying land while leaving the timber value with the logging company was the only financially feasible option at the time. The coalition invited Forterra to help navigate the complex negotiation that was needed in order to establish a county-owned park, restore the forest, preserve Tribal cultural uses, provide the community sustainable recreation opportunities and pay for all of it. Negotiating with optionality, Forterra made sure the agreement gave them the first chance to buy the timber rights if the logging company decided to sell them or the community came together to raise more funds.

Now, a conservation organization negotiating for timber rights is an unusual scenario, but remember, this forest has been logged four times. According to forest ecologists, the process of converting the land from a tree farm to a wild forest can be greatly accelerated by a long-term timber harvest schedule (like thinning the forest every 75 years or so) using ecological forestry methods that increase fire resilience, diversity of species, wildlife habitat and watershed protection. According to the authoritative book, Ecological Forest Management, forest restoration methods include leaving or even adding downed trees for wildlife and watershed protection, creating meadow spaces, removing smaller less healthy trees to give the stronger trees room and resources to grow, planting multiple species of trees and felling trees into streams to improve salmon habitat and hydrology. These steps greatly accelerate the transformation of a tree farm into a much more natural, resilient, functional forest.

With so much of the landscape needing not only preservation but also repair, Port Gamble is a shining example of a place where the scope of conservation is expanding to include human hands working to restore the land. Today, the Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park is the largest county park in Kitsap County but, as with many of Forterra’s most significant projects, the Port Gamble story is long and tortuous, with inevitable setbacks along the way, and it took many smaller steps to reach this point (with many more yet to be taken). In 2011, Forterra was asked by Kitsap County constituents and Tribes to help conserve up to 6,700 acres of land called the Kitsap Forest and Bay – including the Port Gamble Forest. This led to the first success: Kitsap County purchased 535 forested acres and 1.5 miles of shoreline along Port Gamble Bay in early 2014, followed by a 366-acre expansion of North Kitsap Heritage Park. Next, in 2015, the Great Peninsula Conservancy championed the protection of 175 acres at Grover’s Creek Preserve, protecting the headwaters to Miller Bay and providing further connections between trail routes in North Kitsap. In 2016 and then again in 2017, Forterra assisted the county in securing an additional 2,689 acres of the Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park. While these acres could now be managed by Kitsap County in close consultation with the Suquamish and Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribes and input from the local conservation and recreation community, it was on these final acres where the timber company reserved the right to harvest through 2042.

The community celebrated, but after a few years of timber harvests, the parties were interested in going back to the negotiation table to purchase more timber rights. After a year of careful vetting and evaluation with representatives from Rayonier, Kitsap County, Tribes, Forterra and the community, 756 acres of trees of high conservation, cultural and recreation value were selected as part of a three-phased acquisition in 2022. To secure all the negotiated timber rights, the Coalition would once again need to fundraise another $500,000 to be leveraged by $3.925M in county, state and anonymous donor dollars. With the energy and grassroots fundraising power of a new group called Our Forest Fund, this challenge was met in just under three months.

While these steps were each celebration-worthy, some parts of the property are going to see additional industrial logging before they can be managed for restoration and resilience. At the time of this writing, the fifth and final harvest of 2022 has begun. On those acres, repair will have to wait.

Port Gamble is just one of numerous forest properties that Forterra has been involved in through facilitated acquisitions, conservation easements, outright ownership or buy-and-holds, that will greatly benefit from robust ecological forest management over the coming decades. Thanks to the unwavering stewardship of the Tribes and the collaborative mindset of the Kitsap Forest and Bay Coalition, the stage is set to transform and nurture Port Gamble Forest. As is so often the case, land for good can seem elusive in the short term, but a more patient view reveals that a diverse group of people working together over time can ensure a healthy, resilient future for the land, even if it can take a tree’s lifetime to realize it.

A Greek proverb says: A society grows great when old people plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit… A Pacific Northwest version would add: …and negotiates for the preservation of forests yet to grow.

Topher Donahue is an award-winning mountaineer, outdoor adventure journalist and author specializing in the method, culture and evolution of facing challenges and taking risks at the interface of the human and natural world.