The following article is the first of a blog series highlighting Forterra’s history in anticipation of the organization’s rapidly approaching 35th anniversary. This is the start of a year of looking back to look forward, a concept honoring the Sankofa symbol of Ghana’s Akan Tribe which means we should not be afraid to look to our past to help plan our future. This Forterra history project delves into the people, cultures and changes and that shaped the region and the organization and includes historical anecdotes, interviews with visionaries, perspective pieces from a diverse range of experts and celebrates the learning-est moments in Forterra’s history from 1989 through yesterday evening.

Written by Topher Donahue

In the early 2000s, Seattle was celebrating 100 years since the Olmsted Brothers, one of the most renowned landscape architecture firms of all time, had designed the city’s park system. The Olmsted plan included one park for every 3,000 of King County’s 110,000 residents. Since then, the population in the urban areas grew twentyfold. The parks? Not so much. Over the same century, Puget Sound was transformed from one of the planet’s most productive nurseries of living things, to a shadow of its former glory. Once-chubby orcas, a symbol of the bounty and environment of the Pacific Northwest, grew skinny with their skulls protruding sickly as the Chinook salmon populations they relied upon declined. The Duwamish River estuary became so toxic as to receive Superfund designation. The juxtaposition of Olmsted’s vision and the decimation of what had been an exceedingly rich ecosystem was obvious, and begged the question: What will we do to this place in the next century?

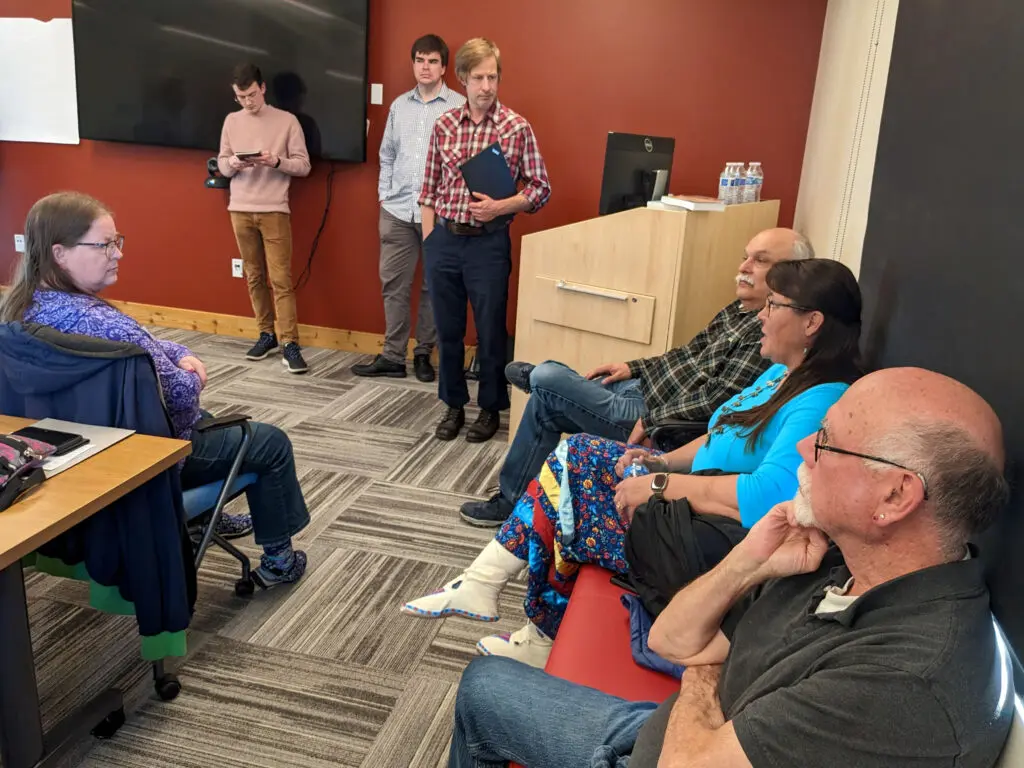

For an answer, Forterra (called the Cascade Land Conservancy at the time) initiated the Cascade Dialogues, a call-and-response with over 3,500 people from diverse communities across the region. The result was combined into a 100-year strategy, the Cascade Agenda, which describes the depth of this input: We have engaged elected and business leaders, civic leaders and stakeholders from Tribes, farmers and foresters, and heard not only what they value in the region but what concerns them about the future. We held a series of teen dialogues to listen to tomorrow’s potential leaders. We have consulted planners, economists and scientists on the critical features of the forests, waters, farms and urban areas of the region.

Part of the genius of the Dialogues was that they inspired people to look beyond the selfishly short timeline of individual profit, goals or biases and the result was an ambitious collective vision. The Agenda targeted specific, measurable goals that included both economy and environment, with specific attention given to 1.3 million acres of working forests, farmlands, parks and shorelines. There was strong agreement that increasing the quality of the cities without expanding their footprint was the best plan; nobody’s hundred-year vision included a house on every acre and developing a high-quality urban environment was just as important as preserving the undeveloped areas. This epiphany changed Forterra’s bearing and set it on a course few, if any, conservation land trusts had ever sailed. Maryanne Tagney, former Forterra board chair and longtime champion of conservation in the region explained, “The shift, becoming more involved in the built community and the human community, was the Cascade Agenda. It was Gene Duvernoy’s baby, his brainchild, and it was innovative. It still is innovative.”

Positive steps were already being taken to restore and preserve the systemic functionality and beauty of the Puget Sound region, but nobody had ever taken the time to gather such extensive input and use it to develop a cohesive strategy. The results turned the “Rooseveltian” definition of conservation on its head, and forever changed Forterra’s role in the region.

This transformation wasn’t just sound bites. Forterra changed its very Articles of Incorporation to include not only a mission of helping land, but also helping people. As Joe Sambataro, who was working with Forterra at the time of the Cascade Dialogues, said during a 2022 interview, “The land trust movement was initially a very white movement that didn’t consider the Tribal ancestral lands or their treaty rights. It was also very privileged. So, there was this evolution of a traditional conservation group trying to be a more holistic, complex organization that does both conservation and community work.”

Initially, there was resistance to including people in conservation work, but with the impacts of climate change and the inseparability of human and natural ecosystems becoming painfully obvious, a sea change gave Forterra’s new heading the boost it needed. As long-time Forterra collaborator Jim Falconer explained, “With the environmental challenge we have, you can’t separate it from the social challenge and economic challenge. You can’t have a healthy environment if you don’t have healthy housing.”

To connect these two historically disparate but in fact inseparable concepts – environment and housing – Forterra, in collaboration with communities, Tribes, developers, foresters and investors, hatched an ambitious plan: Forest to Home, a wood-based, modular housing supply chain that bolsters forest health and carbon sequestration while reinvigorating communities facing severe risk of displacement by providing a more attainable path to home ownership. As with many innovations, communication has proven at least as much of a challenge as the execution.

To start with, how can cutting down trees possibly help the forest? The key here is that the forests that would provide material are tree farms, not old-growth forests. Sure, they look similar out of a car or airplane window, but they’re not. Estimates on how much of the Pacific Northwest’s original old-growth forest has been logged range from 70 to 95 percent , much of which has been replaced by monocultural Douglas fir tree stands. Jerry Franklin, professor emeritus of forest ecosystems at the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington had this to say about the tree farms, “I compare them to a functional forest in the same way a corn or wheat field might compare with a prairie. The plantations we’ve created are extraordinarily artificial.”

By some estimates, there are actually more trees now than there were before logging, but the ecosystem functionality and fire and drought resilience of the forest is vastly reduced. Kirk Hansen, Director of Forestry at Northwest Natural Resources Group, explained, “As we weigh the logistics and costs of addressing some of the ecological problems we face, such as flood mitigation, climate change, endangered species and wildfire, we’re beginning to realize that restoring the ability of nature to resolve these problems is not only less expensive and more effective than engineering solutions, but provides a broader range of co-benefits.”

Rather than clear cutting an area every 35 years, a method called Ecological Forest Management would be used to harvest the wood. This entails mimicking the natural processes of a forest, such as thinning the overcrowded areas, encouraging diversity of species, leaving logs lying on the ground strategically for wildlife habitat and watershed health and most importantly, harvesting on a 70-year cycle, which allows the trees to live through their period of maximum carbon sequestration (around 50 years for the Douglas fir).

The modular building method, coupled with Mass Timber or Cross Laminated Timber (CLT), has been used extensively in Europe for decades and is particularly well-suited to the Ecological Forest Management harvest model. The smaller trees are used for the internal lamina of the solid wood panels, which are shaped and assembled in a factory before transporting them to the building site where they are connected like a giant Lego set. In collaboration with the University of Washington, Forterra coordinated testing that demonstrated excellent fire and earthquake resistance and resulted in legislation that will allow Modular CLT buildings to be as high as 16 stories in the next adoption of building codes – that’s a 175-foot-tall wooden building. While high-rise mass timber buildings do use some concrete and steel, the quantities of these carbon-intensive materials are insignificant compared to typical construction methods. A 10-year life cycle analysis on mass timber construction, done in collaboration between the Beijing Forestry University and the U.S. Forest Service, found that maximizing wood use in buildings could reduce global warming impact by 71% compared to concrete.

At either side of the supply chain are communities; traditional Pacific Northwest logging towns on one end, and neighborhoods, families and businesses at risk of gentrification-driven displacement on the other. As Dan Rankin, Mayor of Darrington, where one of the Modular CLT factories is slated for development, explained, “This is a great idea, something we all need. The timber industry needs it. The urban core needs it. It’s finally this pivotal point where that rural-urban divide starts to soften.”

Studies show that social cohesion of a community is dependent on the quality of a neighborhood – its habitat. After three decades of working to preserve natural habitat, Forterra’s realization that human habitat is part of the same continuum initiated a steep learning curve and growing pains. While working on chronicling Forterra’s history, just about everyone I talked to mentioned the massive organizational education and several people pointed out that these communities’ histories and challenges slapped Forterra in the face with the fact that it isn’t enough to be race neutral – if the role of a land trust involves people, it was time to be actively anti-racist as an organization, and embrace conservation of ancestral and community wisdom and human habitat as fervently as the conservation of forest, water and land.

Thus, there is much more at stake in Forest to Home than proving the viability of the construction method; it is a chance to demonstrate that a strong economy can be distributive across a diverse social ecosystem and regenerative across a biological ecosystem. The place Forterra found itself in the global upheaval of 2022 began with listening to the perspective of thousands of people during the Cascade Dialogues and matured into the opportunity to prove that we don’t have to choose between conservation or economy, environment or people, but rather that these elements are inseparable in the long run and the solutions to our greatest problems can, and simply must, support it all.

Topher Donahue is an award-winning mountaineer, outdoor adventure journalist and author specializing in the method, culture and evolution of facing challenges and taking risks at the interface of the human and natural world.